Research by: Alesya Sokolova

An adapted version of this text in Russian and a game based on it can be found in the special project of “Novaya Gazeta Europe”.

Main Findings

- Distributors of Russian propaganda adapt narratives and content styles to different social groups and use targeting methods to deliver them. We call this phenomenon tailored propaganda.

- One of the key platforms for the distribution of tailored propaganda is the social network VKontakte (VK). 71% of Russians visit it at least once a month. Based on subscription analysis, the VK audience can be divided into 12 clusters of users corresponding to various socio-demographic groups of Russians.

- Tailored propaganda content is created centrally and distributed in networks of entertainment communities on VK with multi-million audiences. For example, in communities for elderly women, the heroism of Russian soldiers is emphasised, while for adult men, the focus is on geopolitical confrontation with the West.

- At least 9% of posts in the most popular VK communities are political. Every eighth popular VK community systematically participates in the distribution of tailored propaganda.

- Tailored propaganda is unevenly effective and popular among different audiences. Older women prefer propaganda posts over non-political ones, teenagers like both types of content equally, while other categories are less interested in propaganda messages compared to regular content.

- Although independent media, activists, and political figures cannot ethically mirror the techniques of propaganda, they can adapt their content to different segments to expand their audience and compete more successfully with pro-Kremlin narratives.

Introduction

According to the Mediascope research centre, 81% of the Russian population used the Internet in 2023, a figure also reflected in surveys conducted by the Levada Centre in 2024. More and more Russians are getting their news from social networks rather than news websites. This is a global trend — social networks allow for more active interaction with content, its authors, and other consumers. They also simplify the possibility of horizontal grassroots association, which poses additional political risks for authoritarian regimes.

One way to mitigate these risks is by blocking social networks and independent media. Almost immediately after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, all independent Russian media were blocked, and expressing any opinion not aligned with the official stance of the authorities was deemed a criminal offence under new laws effectively introducing military censorship. Additionally, Roskomnadzor blocked access to Instagram and Facebook, which were recognized as extremist platforms. There are ongoing discussions about the potential blocking of YouTube, one of the main platforms for distributing opposition content. The administration of the Chinese platform TikTok has independently restricted Russian users' access to certain content.

But blocking alone is not enough. To remain competitive in the online environment, propaganda has to adapt, moving towards more complex and decentralised methods of operation. Controlling TV channels, print, and digital media, the Kremlin expands its propaganda channels to social networks as well. The "patriotic" pro-war agenda is widely represented on Odnoklassniki, VK, and Telegram — the most popular Russian platforms that have benefited from the blocking of foreign competitors. For example, the state-affiliated NGO "Dialogue" manages the pages of schools and other state institutions, filling them with propaganda narratives, even on the personal pages of employees of these organisations. Posts published on behalf of public sector employees and organisations expressed support for Russia's military actions in Ukraine and campaigned for Vladimir Putin ahead of the presidential elections.

Another way to create the appearance of support for the authorities is to use bots and trolls in the comments. Most often, such accounts (usually "real" hired employees) promote an aggressive pro-war agenda on the pages of propaganda publications on social networks. In some VK groups, up to 35% of comments are written by such accounts. Propagandists also use automated bots, with texts likely written by AI. The VK administration seems to condone this, quickly unblocking pro-Kremlin bot accounts if they are blocked.

VK is the most popular social network among Russian users, controlled by the structures of Gazprom and the billionaire from the president's inner circle, Yuri Kovalchuk. According to Mediascope, 71% of Russians over the age of 12 log into their VK profile at least once a month, and on average, 43% of the population visits VK daily. We chose this platform to study the new type of Russian propaganda. VK is suitable for analysis not only because of its popularity but also because its API allows for the collection of open data about users — such as their age and subscriptions.

Our research demonstrates how producers of a new type of online propaganda use non-political communication channels (entertainment communities on VK) and adapt their content to different target audiences — from teenagers to elderly women. These audiences react differently to propaganda messages, but some categories of users like them several times more often than posts without political content. We call this strategy of adapting narratives and content style to different audiences with subsequent targeted placement in non-political channels tailored propaganda.

What Can Be Understood About the Media Consumption of Russians from Their VK Profiles

To analyse tailored propaganda, we identified clusters of users reflecting the main socio-demographic groups and their media consumption patterns. The clusters identified by our method can also be used for other research — for example, analysing the dynamics of propaganda messages or measuring users' attitudes towards various political events.

We chose VK users' subscriptions to various communities as the key parameter for clustering. This is a commonly used parameter — for instance, researchers analyse subscriptions on social networks to determine users' political preferences on X (formerly Twitter) or to identify patterns of extremist content distribution on YouTube. However, we are not aware of any examples of using a similar method to study the VK audience, assess the users’ political preferences, and state propaganda strategies.

Users of the largest national social network do not fully represent the country's population, but we tried to structure our sample to cover the main segments of Russian society. When selecting VK users, we reflected the proportion of demographic characteristics of the Russian population according to Rosstat data. A similar methodology is used in survey research by the Chronicles project and the Levada Centre. The final sample included 30,955 VK users with open profiles. Using data from the VK Bot Monitoring Project Botnadzor and our own machine-learning model, we ensured that the number of bots in our sample did not exceed 1%.

As an additional metric in our analysis, we used the estimated level of users' support for the Russian Armed Forces' military actions in Ukraine. To assess this level, we trained our own model on users who posted pro-war and anti-war hashtags on VK. Based on the analysis of their subscriptions, the model could correctly predict in 76% of cases that a user posted with an anti-war hashtag. For users with pro-war views, the prediction accuracy was 61%.

It is worth noting that the training sample was formed based on users' posts on VK. This factor biases the sample since not every user will openly express their position on a sensitive topic, considering the risk of criminal prosecution. However, the model still makes meaningful predictions of political positions based on a person's subscriptions to different thematic pages on VK. For instance, it showed that war supporters are more often subscribed to United Russia and pro-war bloggers, while opponents are subscribed to Alexei Navalny and other opposition politicians. Similarly, researchers have analysed the political positions of users based on likes on Facebook, subscriptions on X (formerly Twitter), and the news outlets they share links to.

We clustered the obtained sample of 30,955 users based on their subscription vectors to VK communities. This resulted in 13 clusters, one of which included accounts that could not be classified. We analysed the demographic characteristics of users (age, gender, size of the settlement) in each of the remaining 12 clusters based on open information from their profiles. It turned out that each of the clusters, formed based on media consumption, corresponds to a conditional socio-demographic group — their age distribution is unimodal, and in 7 out of 12 clusters, at least 85% of the audience belongs to one gender. It is important to remember that the boundaries of the clusters are quite conditional — for example, some users could be classified both as "young men" and as "urban youth."

For each cluster, we identified the 20 most popular pages that users are subscribed to and studied the content published on them to categorise their media consumption. The BERTopic topic modelling algorithm was used for categorization. Automatic text analysis methods are not always sufficient to adequately determine the meaning of texts, especially considering the prevalence of irony and double meanings, so we conducted additional manual analysis.

Detailed information about the chosen methodology can be found in Appendix 1.

The resulting clusters of VK users are as follows (similar clusters were combined into larger groups):

- "Older Women". Interests: home, interior, cooking recipes, family and children.

- "Retirees": Median age - 65 years, 87% women, pro-war sentiment - 0.56.

- "Women 40+": Median age - 56 years, 99% women, pro-war sentiment - 0.53.

- "Older Men": Median age - 51 years, 99% men, pro-war sentiment - 0.58. Interests: construction, cars, fishing.

- "Young Women": Median age - 38 years, 98% women, pro-war sentiment - 0.46. Interests: home management, cooking recipes, family and children.

- "Young Men": Interests: movies, cars. Subclusters vary significantly.

- "Lads": Median age - 31 years, 87% men, pro-war sentiment - 0.54. Interests: rap, celebrity life, memes.

- "Real Men": Median age - 40 years, 93% men, pro-war sentiment - 0.63. Interests: weapons, construction, cars, USSR.

- "Residents of Large Cities": The most anti-war category.

- "Urban Youth": Median age - 29 years, 59% women, pro-war sentiment - 0.31. Interests: life stories, animals, personal well-being.

- "Business People": Median age - 40 years, 64% women, pro-war sentiment - 0.28. Interests: science, technology, travel, interior design.

- "Teenagers and Young Adults": Users around 20 years old and younger.

- "Teenagers": Median age - 20 years, 69% men, pro-war sentiment - 0.49. Interests: blogging, computer games, music, memes.

- "Young Girls": Median age - 21 years, 96% women, pro-war sentiment - 0.46. Interests: philosophical quotes, memes, self-care, astrology.

- "Z-Patriots": The most pro-war category, consuming almost exclusively pro-Russian political content, including both official media and bloggers. Median age - 62 years, 65% men, pro-war sentiment - 0.59.

- "Movie Buffs": Users who visit VK mainly for movies. Median age - 40 years, 74% men, pro-war sentiment - 0.51.

Narratives of Tailored Propaganda

Among the most popular communities on VK, there are very few purely political ones. This is true for both the overall sample and each user cluster, except for the "Z-patriots", who primarily prefer news and political content. In all other clusters, the top 20 communities never included more than one political page.

However, in some entertainment communities with millions or even tens of millions of followers, propaganda posts are regularly published. Most often, these are images with text (inside and/or above the image), stylistically adapted to the standard content of the community. Entertainment communities for different audiences vary in content, and propaganda adapts its posts — their vocabulary and narratives — accordingly. This is the peculiarity of tailored propaganda.

We identified propaganda content in non-political communities using a combination of machine learning methods (detailed in Appendix 1). According to our final calculations, we classified 9% of all posts in entertainment communities as propaganda. It is worth noting that our method might underestimate the share of political content because not all texts about politics contain characteristic topic-specific marker words, making classification difficult. However, for the purposes of studying propaganda, the accuracy of the chosen method is sufficient.

We studied the narratives of tailored propaganda in the user clusters we identified, reflecting the media consumption patterns of twelve socio-demographic groups. The BERTopic topic modelling technique was used to identify these narratives. It turned out that almost every audience cluster has its own set of propaganda plots and a particular style of information presentation. In some cases, the visual style of propaganda also varies.

- "Older Women"

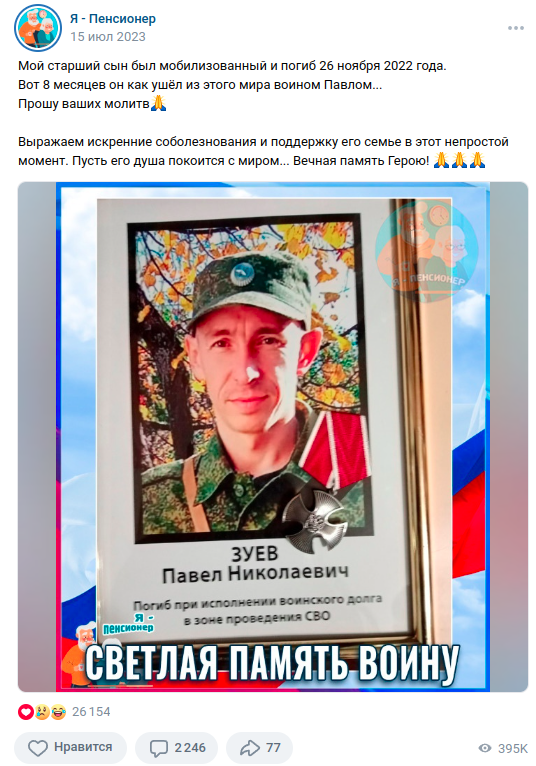

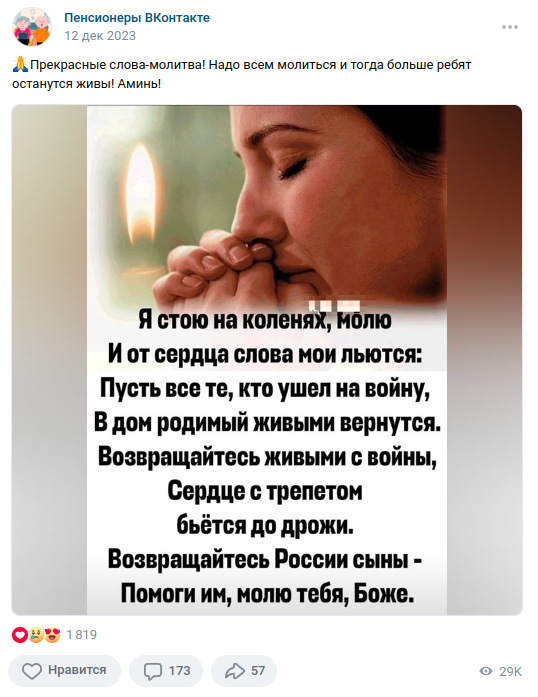

The propaganda content aimed at "retirees" and "women 40+" is almost identical — with the former group having an additional theme of state benefits and pensions. Compared to other clusters, there are fewer posts about the war, the confrontation with the West, and news in general. Instead, there are many obituaries for Russian soldiers who died in Ukraine and eulogies for those who went to fight. The idea of confrontation with the West is not directly expressed: according to the key narrative, Russian men die in a war with some external enemy whose existence does not require additional explanation, and state structures protect the interests of the country.

These posts stand out with a characteristic emotional style and vocabulary. Words like "warrior," "kingdom of heaven," and "good job" are used more often than others. Among older women, such posts receive 2-3 times more likes than other non-political content in the same communities. - "Young Men"

The main theme of propaganda posts for "lads" and "real men" is the political events surrounding the war in Ukraine (not the combat actions themselves). Posts for "young men" regularly feature xenophobic, sexist, and homophobic rhetoric.

Content for the "lads" cluster focuses on domestic politics and legislative news, written in a neutral news style, often without sharp judgments. In the "real men" cluster, the situation is different: the propaganda mainly addresses international politics and the moral character of public figures who support or criticise the war; the style of the posts is more judgmental, harsh, and provocative. - "Residents of Large Cities"

The political content for both clusters ("urban youth" and "business people") is similar. It mimics a liberal and rationalistic identity, with even anti-Western posts formulated in a moderate style. There are significantly fewer sexist, homophobic, and xenophobic posts compared to other clusters. Instead, there are many posts about the positive role of Russia in the development of new technologies, including military ones.

The political agenda surrounding the war in Ukraine remains the most popular topic even in this category, but there are 30-50% fewer posts on this topic compared to the cluster of "young men". - "Teenagers and Young Adults"

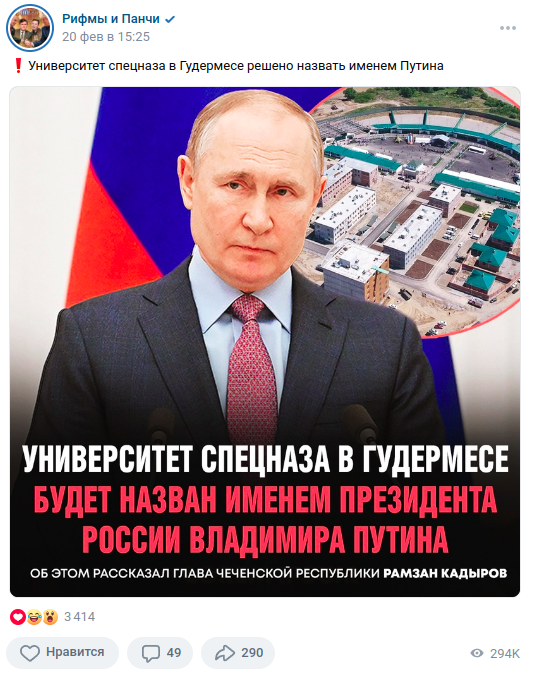

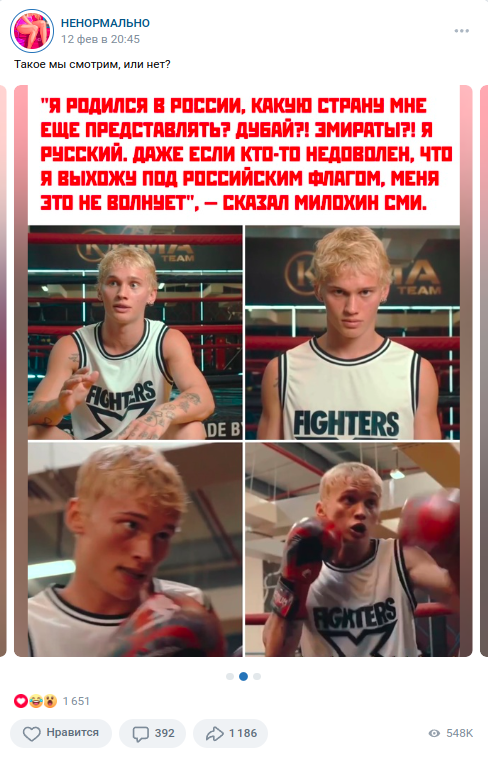

A quarter of all propaganda posts for "teenagers and young adults" are about Putin. Next are the political agenda surrounding the war, news about stars and celebrities, crimes and arrests (including for political reasons), and a bit of domestic and international politics.

Content creators pay a lot of attention to masculine images, presumably attractive to teenagers. They try to create such an image for Vladimir Putin as well.

The authors emphasise the theme of support for Russia by authoritative figures in the West, rather than the idea of confrontation with Europe and the USA. At the same time, chauvinistic rhetoric regarding Ukrainians, migrants within Russia, and LGBT representatives is consistently used in the posts.

Posts in teenager's communities differ significantly from propaganda content in all other clusters. It can be assumed that their creation is handled by a separate structure.

Additional descriptions of the characteristics and media consumption of the clusters can be found in Appendix 2.

How the Network of Pro-Kremlin Pages is Structured

We assume that propaganda content for different audiences (except for teenagers) is disseminated from a single centre. This is indicated by the obvious formal similarity of propaganda posts for very different audiences — all of them are images or a series of images with texts inside and/or above them. Secondary visual elements and the style of presentation may vary, but for some audiences, the narratives chosen by propagandists clearly overlap.

To test the hypothesis of a single coordination centre for propaganda, we decided to select the most "politicised" communities for each audience cluster and study the connections between them. We classified communities with a share of 10 or more propaganda posts out of 500 in the initial sample as politicised. Then we deepened the content sample of such communities from 500 to 3000 posts and calculated the share of propaganda content in this expanded volume.

Our division into audiences was not necessarily set by the group authors — rather, it reflects the people who actually read them.

We built a graph of connections among the considered communities based on the criterion of repeated texts. Given the impossibility of easily copying text from images, repeated texts were either manually transcribed by the administrators of the communities or distributed among the communities from a single source.

On 30 entertainment communities (12.5% of the sample), we found a relatively high proportion of posts with propaganda messages — more than 1% of the content. This means that every eighth popular community on VK systematically participates in disseminating adapted propaganda. Moreover, in 21 of these communities (9% of the sample), we identified posts that were identical in content. According to our hypothesis, such communities are part of a network for distributing adapted propaganda. This network could potentially be much larger, as we only examined the top 20 communities for each cluster, which is a limited sample.

The organisation of such propaganda can take various forms, and the exact mechanism requires further investigation. For instance, a state-affiliated structure might engage in bulk purchasing of native posts in communities. In this scenario, there could be intermediaries such as community administrators who agree to publish adapted posts tailored to their audience, thus explaining the variations in presentation across different communities. Another possibility is the state acquiring individual communities or entire networks of communities. There have been cases where neutral communities unexpectedly shifted towards a pro-government orientation.

The propaganda infrastructure serving the current leadership of Russia lacks a unified apparatus; rather, it is a decentralised system involving numerous entities: foundations, state and non-state organisations, and private individuals. From journalistic investigations, we know about entities like the Internet Development Institute (IRI), which grants funds for creating propaganda; the ANO Dialog, which manages profiles of state agencies and officials on social networks; and the ANO Integration, which develops a network of pro-government Telegram bloggers.

Posts in communities identified within our network appear sufficiently similar to suggest coordination by a single entity, except for the communities targeting teenagers, which exhibit notably different propaganda styles. It seems these are managed by a separate organisation.

How Effective is Tailored Propaganda?

Network propaganda lacks a unified message and may not have a narrow ideological orientation. Its main goal is to achieve citizen loyalty by tailoring messages to target audiences and their preferences. To achieve this, propaganda actively utilises marketing tools: working with big data, studying public opinion and sentiments on social media, assessing risks, and exploring new opportunities. The first prominent case of tailored propaganda was the scandal involving Cambridge Analytica, which used the personal data of Facebook users for targeted political advertising during the Brexit referendum and the US presidential elections.

This is not about replacing one "outdated" type of propaganda with another "more effective" one. Traditional direct propaganda, characteristic of the 20th century, still spreads via radio and television through speeches by politicians and loyal journalists. These two types of propaganda complement each other, and it would be incorrect to consider them separately. Direct propaganda aims to shape specific positions among the mass audience through priming effects (the first position on a given issue heard tends to be more strongly internalised). Network propaganda, including tailored propaganda, influences subtly by filling the information space, supporting, and reinforcing existing consumer opinions.

How effective is such subtle influence? It can be assumed that for many VK users, tailored propaganda is one of the main sources of political information — communities, where it is published, have millions of followers, and each post gains hundreds of thousands of views.

Adoption of a position is not directly reflected in views and likes, making it difficult to measure the success of such propaganda. Propagandistic posts often garner more views, but it cannot be ruled out that they are simply promoted more aggressively.

To assess the popularity of tailored propaganda, we monitored the ratio of likes per view compared to non-political posts in the same communities. The popularity of propaganda varies depending on the cluster — for example, "older women" prefer non-political posts to propagandistic ones, "teenagers" like both types of content roughly equally, whereas other categories show less interest in propaganda messages compared to regular ones.

The effectiveness of tailored propaganda depends on the target audience, indirectly confirmed by our data. However, such propaganda continues to be actively disseminated even among audiences that show no apparent interest in it (for example, young men and residents of large cities). Narratives propagated by tailored propaganda can still be internalised through repeated exposure, despite the lack of visible interest. The simplicity of creating and disseminating tailored propaganda makes it an extremely attractive tool for authoritarian regimes.

VK is fully controlled by the state’s loyal structures, and the ability to publish alternative messages in social network communities is hindered by technical censorship and legal risks. Much of the effectiveness and popularity of propaganda content is due to government control over the information space, repression, and censorship creating a semblance of effectiveness.

Certainly, the influence of propaganda is affected by numerous factors. The content of the narratives offered is important. It presents presents the war as a struggle for peace and the preservation of one's own identity. However, another issue is the lack of sufficiently popular counter-narratives among Russians that do not boil down to accepting responsibility for the crimes of the Russian regime. This is a serious problem, without solving which it is unlikely to expect shifts in public opinion in Russia.

Conclusion

Russian authorities employ all possible means to impose a worldview beneficial to themselves on society. One such method is tailored propaganda. Its narratives and style are adapted to various user segments. This propaganda spreads across entertainment communities on VK with multimillion audiences and is centrally coordinated, as indicated by identical content across different VK communities with varying designs.

To study tailored propaganda, we developed a method for analysing the media consumption of VK users based on their subscriptions. This method can be utilised for investigating other aspects of propaganda and public opinion in Russia. For instance, analysing the dynamics of propaganda narratives or assessing user evaluations of key events, figures, and political plots across different socio-demographic groups. Future research could involve forecasting these evaluations based on open user profile data (we tested such forecasting for support levels during the Ukraine conflict). Enhancing the reliability of such forecasts could involve combining social media data with survey data.

The effectiveness of tailored propaganda is not straightforward: users may become disinterested in repetitive content, and significant interest may not arise among some of the audiences we examined. Likely, this strategy stems from VK's accessibility to propaganda distributors and its low production costs. Similar to traditional methods, tailored propaganda would hardly withstand competition from alternative content in the absence of resource disparities between the state and the opposition.

Due to such disparities and the lack of appealing narratives for Russian audiences, independent media struggle to compete with propaganda. Nonetheless, we believe expanding their audience remains worthwhile. Manipulative techniques in propaganda content — using out-of-context facts to manipulate reader emotions — contradict journalistic standards of information dissemination. However, methods of adapting content to different audience segments — using distinct styles, vocabularies, and channels — could benefit independent media, activists, and opposition politicians.

Content adaptation differs from targeting. Targeting is used to find an audience for produced content, whereas adaptation involves tailoring content production to specific segments. This strategy may entail creating niche media or at least different formats for various social groups. It involves selecting hosts and heroes appealing to the target audience, avoiding ideological language alienating specific groups of people, and employing a broader range of topics and information dissemination formats. A good example of such adaptation is the Feminist Anti-War Resistance case with anti-war postcards in a style familiar to the older generation, distributed via WhatsApp. Developing detailed adaptation strategies for independent media and opposition requires separate research beyond the scope of this text.

Detailed information about the research methods can be found in Appendix 1, and a detailed description of user clusters based on media consumption can be found in Appendix 2.

We would like to thank Alexey Bessudnov, Grigory Asmolov, Maxim Alyukov, Vasily Gatov, Ilya Yablokov, and Anton Mikhaltchuk for their assistance in preparing the article and providing feedback.

An adapted version of this text in Russian, as well as a game based on it, can be found in the special project of "Novaya Gazeta Europe".

This material was prepared with the support of the Reforum project.